"United We Conquer" - the Spean bridge Commando Memorial in the Scottish Highlands

Gameplay

We all know that gameplay must take precedence over real life, if only for the sake of b-b-balance (dread word). Or, at least I hope most of us do know that, but there again...

If you read this blog, I hope you will see that officers in green berets did not lead troops who wore maroon berets (or vice versa). Nor were the Commandos an airborne or gliderborne unit. Though, some Dutch Commandos from No. 10 Commando did apparently jump with the British 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem.

Commandos were not invisible, although they could camouflage themselves, but their friend was nightfall and this was as effective as any magic. Stealth was often a Commandos' aim on smaller raids, but they were equally equipped to be shocktroops: physically fit, determined and hard hitting. They could, however, be vulnerable to more heavily equipped forces with tanks.

Background

The British Commandos were created in June 1940. This was upon the direction of the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, after the Allied defeat culminating in the evacuation at Dunkirk. The Commandos were envisaged as an aggressive raiding force, designed to take the fight back to the Axis.

Each Commando had a lieutenant colonel as the commanding officer and numbered around 450 men, divided into 75 man troops, which were further divided into 15 man sections. Technically, the lieutenant colonels were only on secondment to the Commandos; they retained their own regimental cap badges and remained on their original regimental roll for pay. The Commando force came under the operational control of the Combined Operations Headquarters.

Not unsurprisingly, the Commandos concentrated on beach assaults, since, by 1940, Britain was an island with no land purchase in North West Europe. This meant the Commandos had to be competent in landing ashore from ships, whether from submarines or larger craft, and once ashore, they had to be able to climb whatever cliffs they might face, or deal with any hurdles including wire, mines and pillboxes to get to grips with their assault target. Stealth was practised for dealing with enemy sentries.

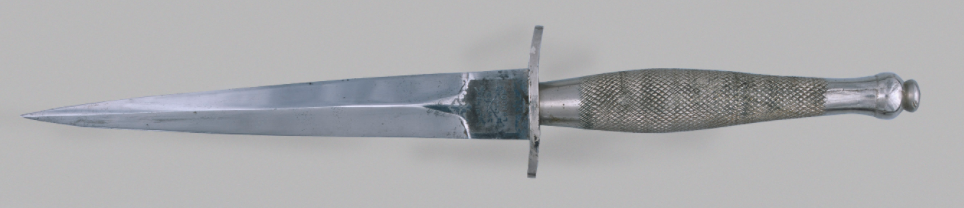

Practice at silent killing with the Commando knife.

Includes cliff climbing in Cornwall, approached from the sea.

The Commando force was organised to provide special service and it was therefore named 'the Special Service Brigade', the acronym of which is 'SS'. The acronym was not a coincidence. The Commandos were designed to be shock troops. The SS designation continued until after D-Day in June 1944, but subsequently, for evident propaganda/PR reasons, the SS nomenclature was dropped by the end of 1944, to become the Commando Brigade.

Smaller units which derived from the Special Service Brigade included the Special Air Service (SAS) and the Special Boat Squadron (SBS), whose founders had served in one Commando or another, however briefly.

On 22 June 1940, No. 2 Commando assumed parachute duties, and on 21 November it was re-designated the 11th Special Air Service Battalion, with a parachute and glider wing. As the formation grew larger, it was renamed the 1st Parachute battalion and formed the basis of expansion for the new Airborne divisions (which adopted a maroon beret).

Recruitment

The Commando base was established at Achnacarry, Lochaber in the West of Scotland, near to Fort William.

Lochaber Commando training at Achnacarry - interspersed with Veterans' comments.

All Commandos were initially volunteers, who were awarded the Green Beret if they passed the course. They wore their original unit cap badge with the beret. Additionally, on passing the course, they were awarded the Commando dagger. As the war progressed, some Commandos adopted a more cohesive approach to cap badges, but as you will see below, there was still independence of approach from one Commando to another.

As the Commandos became successful, their area of operations stretched across the world, and there were Commandos fighting in places as far apart as North West Europe, North Africa, Italy, Madagascar and Assam in Bengal. This inevitably diluted numbers. So in 1943, a Royal Marine division was converted to become Commandos en masse. There was a certain rivalry between the Army commandos who were all hand-picked volunteers from all branches of the service, as against the professional RM officers, who apparently regarded the Army Commandos as enthusiastic, somewhat indisciplined amateurs.

The Fairburn-Sykes Fighting Knife

The Fairbairn-Sykes ('F-S') dagger had a big influence on the insignia design for commando and special forces units.

The Special Service brigade HQ incorporated two F-S knives with the red 'SS'forming the S guards for the knives. The brigade's signals unit incorporated a lightning bolt crossed with an F-S dagger. The dagger is not part of the SAS cap badge: their blade is Excalibur.

No. 2 Commando used an F-S on its cap badge and shoulder insignia. No. 5 Commando used the Roman numeral V between crossed F-S daggers.

When Royal Marine units were coopted into the commandos, they carried a triangular shoulder insignia with the dagger point-up.

When Royal Marine units were coopted into the commandos, they carried a triangular shoulder insignia with the dagger point-up.The French Commandos Marine used a shield with a sailing ship, the F-S dagger, and the Cross of Lorraine for their beret badge. The WWII Canadian parachute battalion had officers' collar insignia which incorporated the F-S dagger in a hand coming from a cloud.

This was a Commando beret; it is not standard:

Commandos Under Training

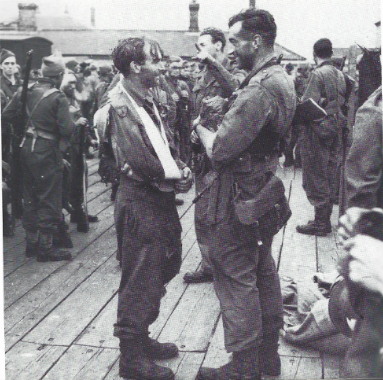

US Caotain Lloyd Marr, braces himself for training in 1943 under the auspices of the Commandant of the Commando Training Depot, Lt Colonel Vaughan as well as Lt Colonel the 15th Lord Lovat (at the time OC no. 4 Commando, later Brigadier i/c 1st Special Brigade). The 29th Provisional US Ranger Bn. attended Achnacarry in 2 course intakes during Feb/March 1943 and May 1943. Captain, later Major, Lloyd M. Marr was the 29th Prov. US Ranger Bn. Executive officer and 2i/c.

United States Army Rangers and Commandos from France, the Netherlands, Norway, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Belgium trained at Achnacarry. Each training course culminated in an "opposed landing" exercise around the area of nearby Bunarkaig on Loch Lochy. As live ammunition was used, there were some casualties while training. Approximately 25,000 commandos completed training at the centre during the four years it was in use.

Training under fire on a toggle rope bridge

No. 10 (Inter Allied) of the Commando regiments might be mentioned at this point. By the end of the war, they had become the largest Commando force in the British Army and included volunteers from France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, Norway, Denmark, Poland and Yugoslavia. Men from the Commando served in the Mediterranean, Scandinavia, Burma and Western Europe during the Second World War, mostly in small numbers attached to other formations.

Men from No. 6 Polish Troop on exercise in Scotland 1943. (Probably Privates Katitof and Barton). Note the No. 10 Commando, Poland shoulder flashes, as well as the combined operations arm badges.

Polish No. 10 Commandos under training (mostly military)

There was another group of volunteers in X Troop which contained Germans and Austrians who had escaped from Nazi Germany, often Jewish. All members of X troop adopted British names and false personnel histories. A total of 130 men served in X Troop, but they never fought as a complete unit. They provided valuable service to other formations as interpreters and interrogators. The troop lost 21 men killed and a further 22 wounded.

Under training - without tin helmets.

Members of No. 3 Commando - 1944 street fighting course in bombed-out East London. Note! Not invisible and not teleporting.

Any breach of discipline could mean being 'returned to unit' (RTU), which was considered a disgrace. Army Commandos had to develop self-reliance and initiative, part of which meant arriving on parade when required at the right time, with the proper kit.

Early Operations

Experimental small-scale raids on the coast of France started with an inauspicious raid in the Channel Islands, but with experience, there resulted the seaborne raid on the Norwegian Lofoten islands in 1941.

Another small scale raid which was successful from a propaganda aspect was the Cockleshell Heroes (see link), being a canoe raiding expedition up the River Gironde to Bordeaux, to destroy Axis ships in December 1942.

On a larger scale, the Commandos became better-known for their participation in the St Nazaire Raid in France, in March 1942, as well as their participation in the murderous Dieppe assault in August 1942, which resulted in large scale losses for the Canadian army and was considered a disaster by the Commandos. (The outcome of the Dieppe Raid was that an invasion of North West Europe was probably set back by at least a year.)

No. 4 Commando returning from the Dieppe Raid.

All in all, there were 57 Commando raids from 1940 to 1944, with 37 against the coast of France. The smaller raids ended in mid-1944 on the orders of Major General Robert Laycock, who suggested that they were no longer as effective and only resulted in the Germans strengthening their beach defences. Something that could be extremely detrimental to Allied plans for a seaborne invasion.

Lord Lovat and Commandos returning from the Dieppe raid

After Dieppe, there was a Commando raid on the Channel Island of Sark in October 1942. The results of that raid resulted in 'the Hitler Order'.

| !In future, all terror and sabotage troops of the British and their accomplices, who do not act like soldiers but rather like bandits, will be treated as such by the German troops and will be ruthlessly eliminated in battle, wherever they appear. |

Put simply, this was a death warrant from then on for captured Commandos (even though in uniform), and it constituted another hazard. Fight and win, then escape - because otherwise, there was only certain death, if captured.

D-Day and North Western Europe Campaign

It was Lord Lovat who led the 1st Special Service Brigade ashore at D-Day with his Piper, comprising 3, 4 and 6 Commando, as well as 200 French Marines from 10 Commando and 45 Royal Marine Commando. Also in the assault was the 47th Special Service Brigade comprising 41, 46, 47 and 48 Royal Marine Commandos.

Landing on Queen Red Beach, Sword in Normandy: Piper Millin is in the foreground at the right, and you can see the pipes ready to play. Meanwhile, Lord Lovat is wading through the water, to the right of the column of men in the sea.

The Special Service Brigades' assault was successful, but thereafter the Army had a problem with its Commandos: it had a valuable infantry fighting force, which was too highly motivated and trained to be used as ordinary infantry. In consequence, the Brigades were mostly only used thereafter as shock troops for violent assault, such as the beginning of the recapture of the Scheldt at Walcheren (4th Special Service Brigade, as well as French, Dutch and Belgians from 10 Commando) on 1st November 1944, or Operation Blackcock in the Roer triangle in January 1945, or the assault over the Rhine at Wesel in March 1945.

French Commandos of no.10 Commando on D-Day

Post war interview with Lord Lovat and his piper, Bill Millin.

Smaller sections of specialists such as Commando Mines and Demolitions teams were often used to assist front line infantry. In such an incident in Holland was my late father-in-law's jeep blown up over a mine, as he rushed his team forward to clear mines in front of a Polish unit. His natural impetuosity, combined with Polish inability to express themselves clearly as to the whereabouts of the mines, is a situation easy to imagine from these forums. However, he was saved from a worse fate by the fact that most Jeeps carried sandbags on the floor, as part of their anti-mine protection. Something which more modern soldiering seems to have ignored.

Disbandment - 1945

The British Generals' dislike of denuding ordinary infantry units, by extracting committed fighters to the Commandos and other aggressive units like the airborne was rationalised soon after the war's end: dislike of 'elite' units outside the Guards led to degradation of special forces. The British Army Commandos were completely disbanded, as were the SAS and SBS, as well as other formations like 'Popski's Private Army' and the Long Range Desert Group, leaving only the Royal Marine Commandos.

The British Generals' dislike of denuding ordinary infantry units, by extracting committed fighters to the Commandos and other aggressive units like the airborne was rationalised soon after the war's end: dislike of 'elite' units outside the Guards led to degradation of special forces. The British Army Commandos were completely disbanded, as were the SAS and SBS, as well as other formations like 'Popski's Private Army' and the Long Range Desert Group, leaving only the Royal Marine Commandos. Research has tended to prove what the British Generals must have known: that in most infantry units, there is a small band of fighters who provide impetus and example for the their comrades. If you denude ordinary units of committed men who go to fight for units like the Commandos, you may have shock troops who could and did stand comparison with such units as the SS, but too often it left a lot of the ordinary 'poor bloody infantry', who were less resilient in tough situations, without 'natural leaders'.

That some smaller units like the SAS were reconstituted within a few years is another story. But the Army Commandos were sadly no more.

The Commando Memorial looks out over the former training grounds near Fort William

Appendix

Having edited various News posts and some Guides on these forums, and having played through the British faction in COH1 and COH2, I thought it might be helpful to write this blog about the WWII Commandos - what they did in real life, and what the Commandos never did in real life. I have confined my observations mostly to North West Europe, so there should be plenty of scope, if somebody wants to write about a Commando operation in depth in North West Europe, or an action outside NW Europe.

I apologise if I have not gone into masses of detail such as Orders of Battle - the subject is too vast for that. Equally, I also apologise to those who find lists of infantry units boring: I have tried to keep those to a minimum.

We all participate in the COH franchise because it is fun, and often immersive. Nevertheless, in the interests of balance (that word again!), history can become distorted and so I have tried to rebalance this with regards to the Commandos: they were not supermen, nor could they win the vicious 'game' of war on their own.

As best I can, I have tried to provide an insight into what the Commandos were about, and how they were held in high regard, at least by their own side. It really does not matter if you jump from flak-filled skies, or ride onto a beach in a small boat which faces a choppy sea on fire, and/or multiple machine guns and the engines of war, and/or mines, wire and pillboxes. Ultimately, it takes guts and determination to succeed, and they were the first in line.

I have left some book links for anybody who might want to read about the subject in far greater depth than I can offer here. One is a memoir by Lord Lovat: March Past, another is a memoir by his right hand man, Brigadier Derek Mills-Roberts (who started the war as a trainee lawyer), the third is by Durnford-Slater who was in at the beginning of the formation, and the last is written by a junior officer about Achnacarry training: Castle Keep. Because these memoirs were written decades ago, their availability is now harder to source, and reflects itself in the price. You might however be able to borrow a copy from a good public library.

Bagpipe tunes played by the Piper Millen to help inspire the Commandos on D-Day

cblanco ★

cblanco ★  보드카 중대

보드카 중대  VonManteuffel

VonManteuffel  Heartless Jäger

Heartless Jäger